The ethics of 'editing' nature [View all]

https://aeon.co/essays/should-we-intervene-in-evolution-the-ethics-of-editing-nature

https://aeon.co/essays/should-we-intervene-in-evolution-the-ethics-of-editing-nature

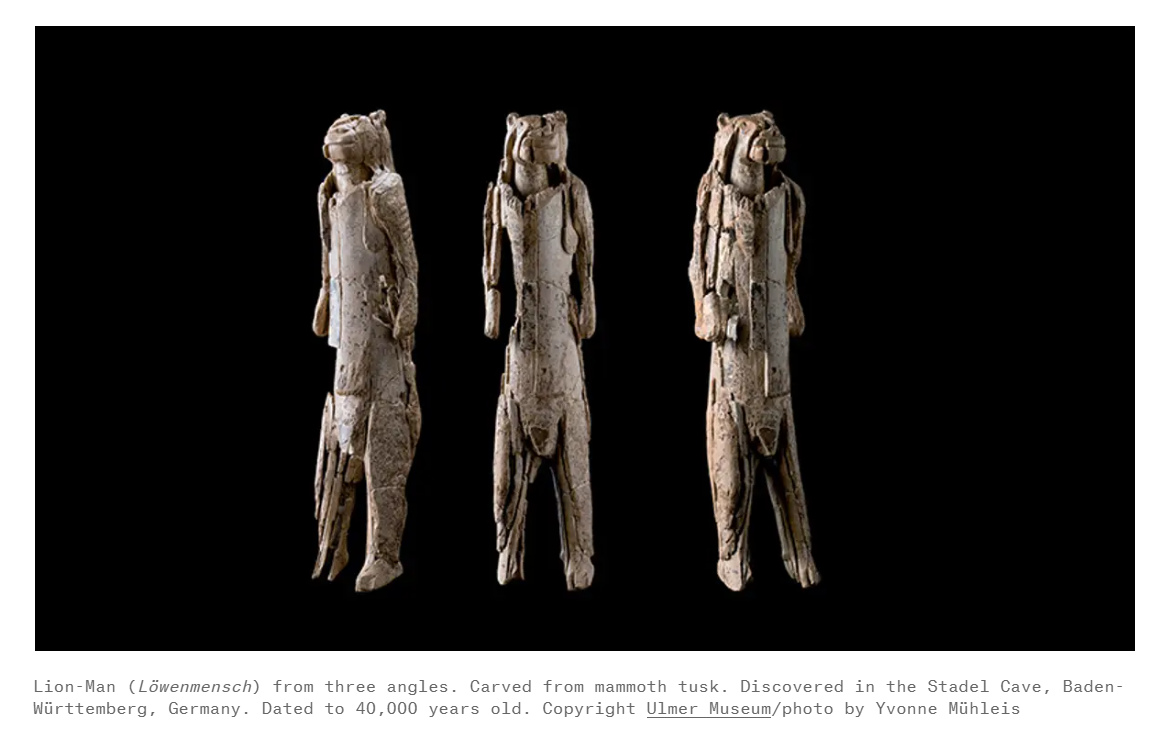

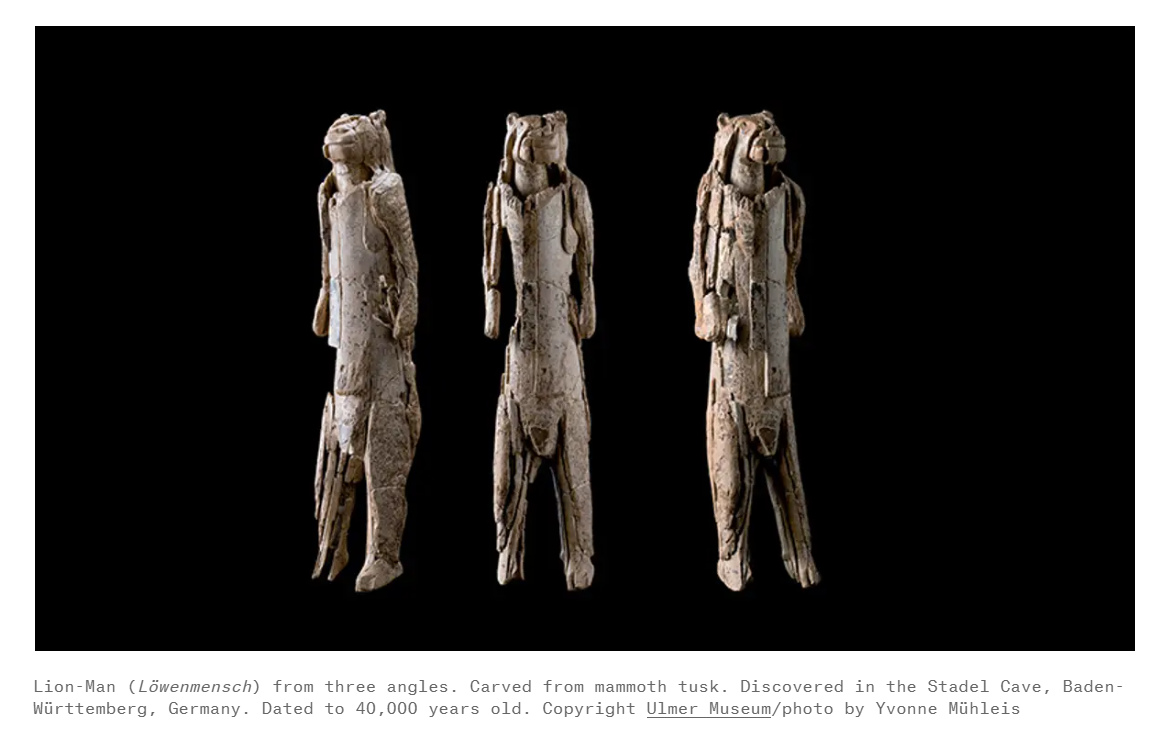

At the end of August 1939, the German archaeologist Otto Völzing discovered around 200 fragments of carved mammoth ivory at the back of a cave in southern Germany. With war just a week away, Völzing’s find was hurriedly collected in a box, where it lay unnoticed in a museum archive for decades. It wasn’t until the 1960s, when the shards were inventoried, that something astonishing emerged out of the heap of broken pieces. They formed an incomplete figurine, with a chimeric mix of features: the body of person, and the head and forearms of a cave lion. Subsequent excavations in the 1970s found further pieces of what has come to be called the Lion-Man of Hohlenstein-Stadel. Carved from a mammoth tusk around 40,000 years ago, it is one of the earliest examples of the human capacity to imagine forms that don’t exist in nature.

Every age of human history since the Lion-Man has tried to think beyond nature. In Hesiod’s

Theogony, composed around 700 BCE, the chimera was a compound being with the head of a lion, the body of a dragon, and a snake’s-head tail (and an extra goat’s head protruding from its back for good measure). In W B Yeats’s poem ‘The Second Coming’ (1920), a similar ‘rough beast’ is a harbinger of ruin.

A decorated plate featuring a chimera. Apulia, Italy, 350-340 BCE. Courtesy Louvre, Paris

A decorated plate featuring a chimera. Apulia, Italy, 350-340 BCE. Courtesy Louvre, Paris

In our own time, the chimeras are something different. Living things in every part of the biosphere have been forced by climate change, pollution and the spread of non-native species to

adapt their bodies and behaviours to a human planet. They may not have visibly merged forms like the Lion-Man, but they do bear the impression of another species: us. It wasn’t our intention that humanity would become the planet’s greatest

evolutionary force; yet the fact that we are confronts us with an urgent and difficult question. Some animals, plants and insects can adapt but, for many, the pace of change is too great. Should we try to save them by deliberately intervening in their evolution?

The emergence of precision

gene-editing technology like CRISPR-Cas9, which acts like a molecular scalpel so fine it can swap even single letters of DNA, has made a world of chimeric species possible. For some, splicing the DNA of extinct megafauna like

dire wolves and

mammoth into grey wolves or Asian elephants is an opportunity to resurrect a long-vanished world. But with synthetic biology we could potentially save the world of the present, intervening in the evolution of vulnerable species so they can survive changing climates and collapsing ecosystems. Plants could be edited to cope with drought, or to improve photosynthesis in crops. Microbes could be programmed to sense pollution and consume toxins, even the

marine plastic that gluts the digestive tracts of seabirds. With assisted evolution, we might spare

coral reef systems from collapse.

snip