Welcome to DU!

The truly grassroots left-of-center political community where regular people, not algorithms, drive the discussions and set the standards.

Join the community:

Create a free account

Support DU (and get rid of ads!):

Become a Star Member

Latest Breaking News

Editorials & Other Articles

General Discussion

The DU Lounge

All Forums

Issue Forums

Culture Forums

Alliance Forums

Region Forums

Support Forums

Help & Search

The ethics of 'editing' nature

https://aeon.co/essays/should-we-intervene-in-evolution-the-ethics-of-editing-nature

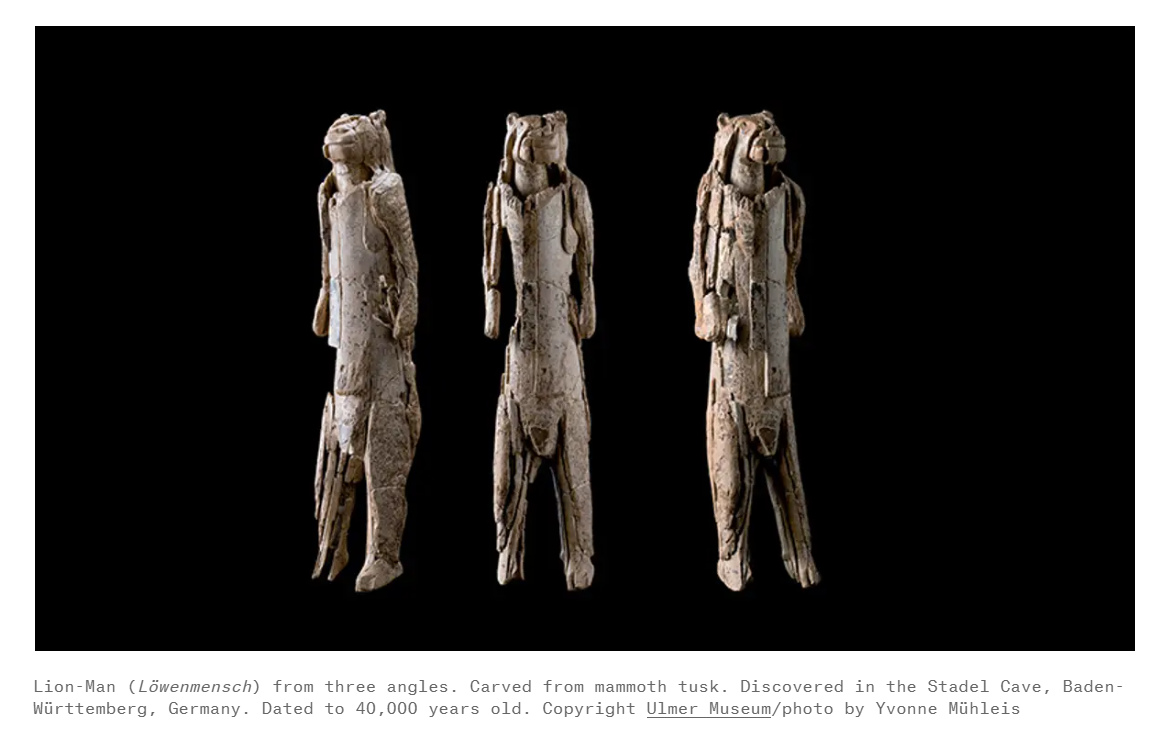

At the end of August 1939, the German archaeologist Otto Völzing discovered around 200 fragments of carved mammoth ivory at the back of a cave in southern Germany. With war just a week away, Völzing’s find was hurriedly collected in a box, where it lay unnoticed in a museum archive for decades. It wasn’t until the 1960s, when the shards were inventoried, that something astonishing emerged out of the heap of broken pieces. They formed an incomplete figurine, with a chimeric mix of features: the body of person, and the head and forearms of a cave lion. Subsequent excavations in the 1970s found further pieces of what has come to be called the Lion-Man of Hohlenstein-Stadel. Carved from a mammoth tusk around 40,000 years ago, it is one of the earliest examples of the human capacity to imagine forms that don’t exist in nature.

Every age of human history since the Lion-Man has tried to think beyond nature. In Hesiod’s Theogony, composed around 700 BCE, the chimera was a compound being with the head of a lion, the body of a dragon, and a snake’s-head tail (and an extra goat’s head protruding from its back for good measure). In W B Yeats’s poem ‘The Second Coming’ (1920), a similar ‘rough beast’ is a harbinger of ruin.

A decorated plate featuring a chimera. Apulia, Italy, 350-340 BCE. Courtesy Louvre, Paris

In our own time, the chimeras are something different. Living things in every part of the biosphere have been forced by climate change, pollution and the spread of non-native species to adapt their bodies and behaviours to a human planet. They may not have visibly merged forms like the Lion-Man, but they do bear the impression of another species: us. It wasn’t our intention that humanity would become the planet’s greatest evolutionary force; yet the fact that we are confronts us with an urgent and difficult question. Some animals, plants and insects can adapt but, for many, the pace of change is too great. Should we try to save them by deliberately intervening in their evolution?

The emergence of precision gene-editing technology like CRISPR-Cas9, which acts like a molecular scalpel so fine it can swap even single letters of DNA, has made a world of chimeric species possible. For some, splicing the DNA of extinct megafauna like dire wolves and mammoth into grey wolves or Asian elephants is an opportunity to resurrect a long-vanished world. But with synthetic biology we could potentially save the world of the present, intervening in the evolution of vulnerable species so they can survive changing climates and collapsing ecosystems. Plants could be edited to cope with drought, or to improve photosynthesis in crops. Microbes could be programmed to sense pollution and consume toxins, even the marine plastic that gluts the digestive tracts of seabirds. With assisted evolution, we might spare coral reef systems from collapse.

snip

2 replies

= new reply since forum marked as read

Highlight:

NoneDon't highlight anything

5 newestHighlight 5 most recent replies

= new reply since forum marked as read

Highlight:

NoneDon't highlight anything

5 newestHighlight 5 most recent replies

The ethics of 'editing' nature (Original Post)

Celerity

Saturday

OP

Altering is not saving. WH ballroom is not saving WH. Species are not individuals.

Bernardo de La Paz

Saturday

#1

Bernardo de La Paz

(58,853 posts)1. Altering is not saving. WH ballroom is not saving WH. Species are not individuals.

Help species in other ways like introducing into areas that would be accomodative (keeping in mind "invasive species" issues).

Definitely freeze multiple embryos.

Response to Celerity (Original post)

anciano This message was self-deleted by its author.