Pets

Related: About this forumThe Microbiomes of Indoor, Feral, and Indoor/Outdoor Cats: Implications for Health and Antibiotic Resistance.

This may be a little "sciency" for this forum, but I came across an interesting article in my general reading: Composition, Antibiotic Resistance, and Functionality of the Gut Microbiome in Urban Cats Ricardo David Avellán-Llaguno, An Xie, Alex Ujong Obeten, Zhizhen Pan, Yiyue Zhang, GuoZhu Ye, Xin Sun, and Qiansheng Huang Environmental Science & Technology 2025 59 (32), 17258-17274.

I thought I'd post it with brief commentary.

(We are struggling to make sure the impetuous kitten we recently adopted with his Mom grows up to be an indoor cat; he's very curious about the great outdoors, having spent his whole life previous to adoption in a cage, and often runs toward the door when we open it. His Mom, by contrast, possibly previously owned before being abandoned, is perfectly happy indoors. I'm not sure Harry, the kitten would understand it if we explained to him the health risks of going outdoors.)

From the introductory text of the article:

Researchers have identified bacterial (7) and viral (8) zoonotic pathogens in cats. Notably, bacteriological studies show that 75% of cat bite incidents reveal Pasteurella species, which pose health risks to humans. (9) Urban environments are critical in the spread of these pathogens, exemplified by bacteria like Bartonella henselae, (10) presenting significant concerns for public health and urban ecology. Moreover, the diversification of Clostridioides difficile and Clostridium perfringens, categorized as zoonotic pathogens, has been documented in cats and other animals. (11,12) Urban cat populations, notably free-roaming cats, are a significant source of pathogens and their dispersion. (13)

Additionally, studies on antibiotic resistance in cats and dogs indicate the presence of ARGs and mobile genetic elements (MGEs), underscoring the risk of transmitting resistant bacteria from pets to humans. (14,15) The growing population of pet animals highlights the importance of understanding the epidemiology of bacteria in cats, particularly concerning the spread of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and zoonotic transmission. (16,17) Research has focused on the genetic mechanisms of antibiotic resistance, revealing MGEs within the feline gut that complicate the issue, although knowledge gaps persist. (18,19) Identifying gut microbial taxa linked to antibiotic resistance remains limited. Nonetheless, some bacterial groups have been referenced as potential contributors to antibiotic resistance. (20)

The misuse of antibiotics has become prevalent in both human and veterinary medicine, leading to the proliferation of antibiotic-resistant bacteria. (21) Improper antibiotic administration to urban animals can disrupt the natural balance of their microbiome, increasing susceptibility to diseases. (22,23) Contamination of environments due to antibiotic residues further complicates wildlife health and contributes to antibiotic resistance. (24) It is crucial to emphasize responsible antibiotic use in veterinary medicine and to raise awareness of its potential impacts on urban wildlife. (25)

Based on the established grouping criteria, we propose the following hypothesis: (1) The unstable food sources and interaction with a free-range environment have increased the potential health risks associated with the microbiome in the gut of cats, (2) Food serves as the primary environmental filtering factor compared to living conditions, leading to a more clustered microbiome composition in FRD cats when compared to D cats, as opposed to FR cats...

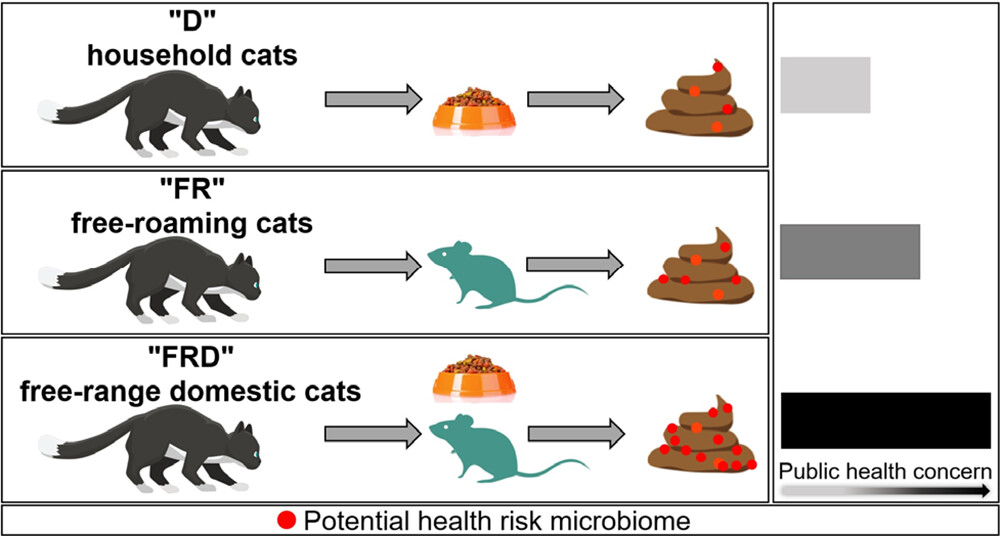

A graphic from the paper's abstract:

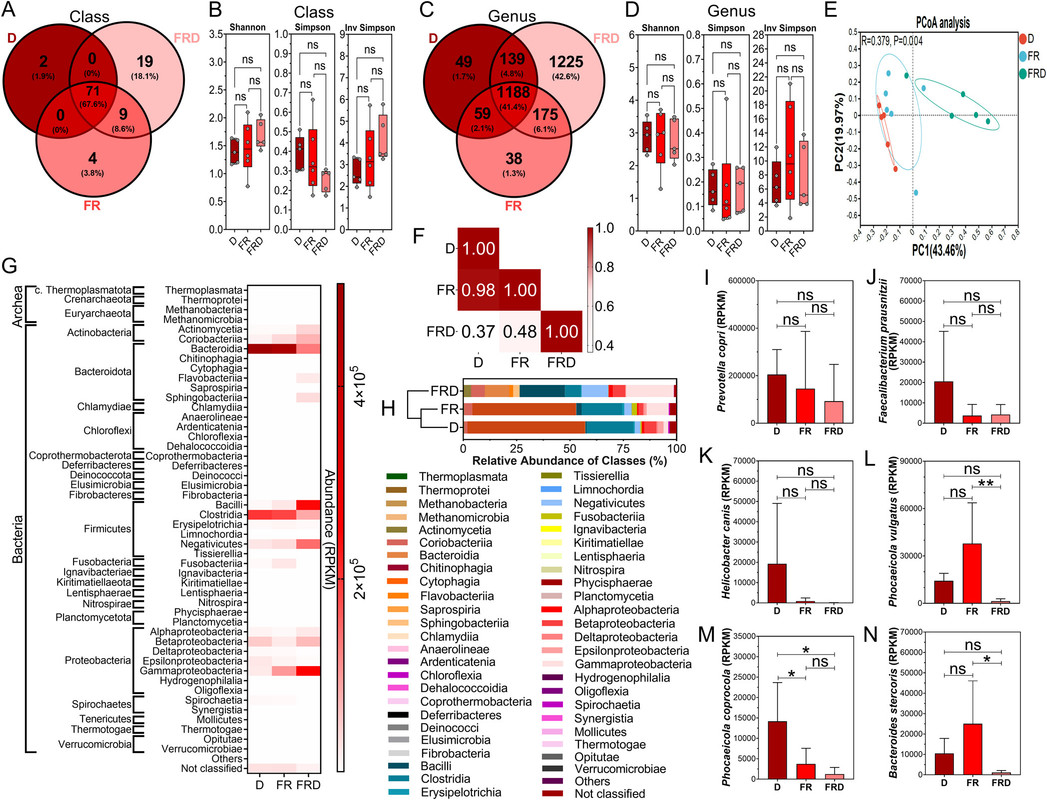

A "sciency" graphic on the breakdown of organisms in the three cat classifications:

The caption:

Some other text from the discussion:

From the conclusion:

We have twice adopted feral cats; we actually moved for the first to a "pets allowed" apartment, but unfortunately she was not willing to remain an indoor cat, and was paralyzed by a car shortly after we moved and we had to put her down.

The second was a polydactyl cat, who tested positive to toxoplasmosis when my wife was pregnant with my first son. Happily there was a lot of interest in adopting him, even with the positive test, and so we were able to quickly find a home for him.

I thought this might be good to know. If you adopt a feral cat, visits to the vet are advised.

bamagal62

(4,370 posts)That never could become a house cat. After about a week or two she decided to stalk our daughter. It was brutal and resulted in a bite. My daughter was 15 at the time and is a very gentle, kind person. Since it had only been a short time from “rescuing” her, we had her spayed and released her back into the area. Never saw her again. It was quite odd. I’ve never had a cat that was mean. This one was mean.

Deep State Witch

(12,618 posts)We foster cats through our local rescue group. So often these cats have poop issues, even if they were cared for by a colony caretaker. We keep Fortiflora probiotics on hand and give them to any of the fosters that were outdoors for any length of time. Our current foster had a cut on his neck and was given a long-acting antibiotic shot when the SPCA stitched it up. His poops were rather noxious and soft. They still are, but not as bad. And then there was the one foster that we had this time 2 years ago who had both worms and giardia. She literally had a poop explosion all over the foster room! Poor girl.