Six centuries of secularism

When the first ‘how-to’ books began to explain the way the world worked, they paved the way for science and secularism

https://aeon.co/essays/six-centuries-of-secularity-began-with-the-first-how-to-books

When the first ‘how-to’ books began to explain the way the world worked, they paved the way for science and secularism

https://aeon.co/essays/six-centuries-of-secularity-began-with-the-first-how-to-books

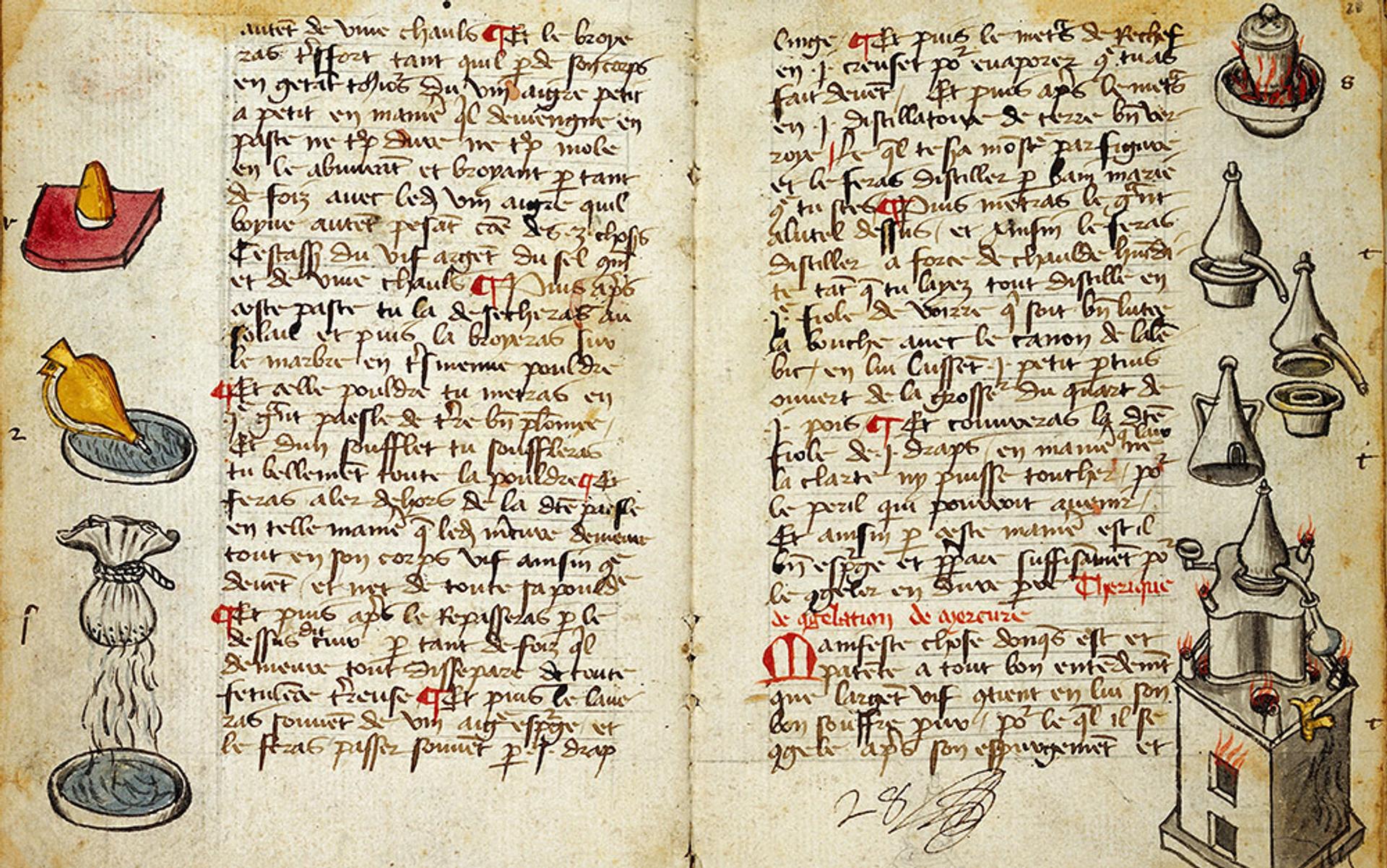

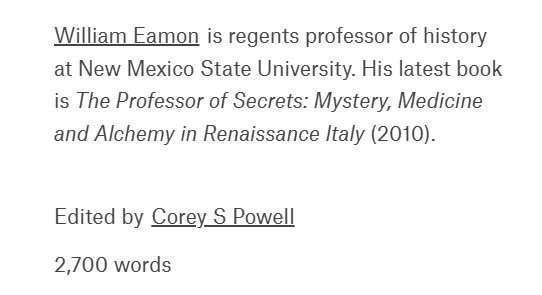

An illuminated page from a book on alchemical processes and receipts Ymage de vie Raymundus Lullius, late 15th century. Photo courtesy Wellcome Images

An illuminated page from a book on alchemical processes and receipts Ymage de vie Raymundus Lullius, late 15th century. Photo courtesy Wellcome Images

Every presidential election cycle brings candidates touting their religious convictions. Being too secular is rarely a winning political strategy. In fact, Bernie Sanders might have been the first openly secular major presidential candidate in the history of the United States. Even Thomas Jefferson, though not a Christian, was a deist who firmly believed in a creator God. Pressed by the late-night television host Jimmy Kimmel, Sanders said: ‘What I believe in, and what my spirituality is about, is that we’re all in this together.’ That iconoclasm was part of his appeal, but probably part of his downfall, too.

With conservatives decrying what they see as creeping secularism, and liberals warning of attacks on the separation of church and state, one gets the impression that many Americans believe that secularism is something quite new, a product of declining morals or aftershocks from the cultural revolution of the 1960s. Yet the roots of secularism in the West run far deeper, deeper even than Jefferson and the Age of Reason. Most historians agree that secularisation took hold in the period known as the ‘early modern’ – the era between about 1500 and 1750, when science, capitalism, religious crisis and the growth of centralised states coalesced to reshape Western consciousness.

The religious implications of secularism are often misconstrued, too. Secularisation did not mean godlessness; for the most part, early modern Europeans were profoundly Christian. It was rather that the boundary between the religious and the secular became more distinct than before. As the 17th-century English philosopher Sir Thomas Browne put it, humans live ‘in divided and distinguished worlds’. The sphere of religion was diminished, so that many of the hopes and fears formerly expressed in religious terms became expressed in worldly terms. For better or worse, secularisation rested on the realisation that eternal truths are inaccessible to the intellect; only the limited insights afforded by experience in this world are relevant to the earthly career of the human race.

Accompanying the secularisation of Western society were dramatic changes in material life. It was visible everywhere in the marketplace. The newly emerging secular world was a world exploding with things: spices, tobacco and chocolate from the New World; silk and turquoise from Ottoman Turkey; porcelain and embroidery from the distant Far East; hotchpotches of things collected and displayed in pharmacies and private curiosity cabinets, such as stuffed armadillos, Native American featherwork, and unicorns’ horns (narwhal tusks, in reality).

snip